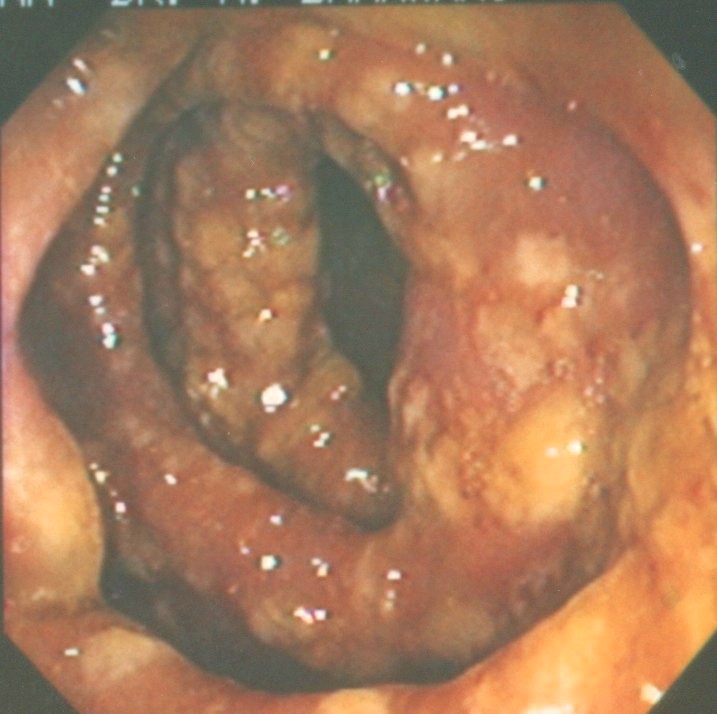

Photograph shows colon acutely inflamed – red, swollen with white patches of psuedo membranes. An extreme case of C.difficile colitis – also known as pseudomembranous colitis.

In 1935, Hall and O’Toole first isolated a bacterium from the stool of healthy newborns. They named it Bacillus difficilis to reflect the difficulties they encountered in its isolation and culture. Now, after 77 years, we are unable to contain the growth and spread of the same bacterium, renamed as Clostridium difficile.

C. difficile is a frequent cause of infectious colitis, usually occurring as a complication of antibiotic therapy. Elderly hospitalized patients and other vulnerable patients are easy victims. Then there is community acquired disease in people who have not taken antibiotics.

This is not surprising, since C. difficile has been cultured from the stool of three per cent of healthy adults and up to 80 per cent of healthy newborns and infants. Patients who are discharged from the hospital or the visitors to the hospitals and nursing homes can pick up these bugs and spread it in the community. Hand hygiene plays an important role in prevention.

There is not much information out there on C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) in pregnancy. I did find one article: Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: an emerging threat to pregnant women (American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology – June 2008). The article says that largely due to their young age and overall good health, pregnant women have historically been at low risk for developing CDAD.

In a retrospective study of 74,120 admissions to an obstetrics and gynecology service over 10 years, only 18 women (0.02 per cent) developed CDAD. However, a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report reported 10 cases of peripartum (occurring during the last month of pregnancy or the first few months after delivery) disease from four states. Among these women, 40 per cent required hospitalization, 50 per cent experienced relapse, and one died.

Since CDAD is not a reportable disease, it is difficult to know the exact incidence of the problem and its complications in pregnant patients. It is a serious problem and CDAD should be taken seriously in this particular population and to raise the level of concern and vigilance among physicians.

Patients with CDAD can have a broad range of symptoms. Patient may be asymptomatic carrier or in an extreme situation may have life-threatening colitis.

Approximately, three per cent of adults and 80 per cent of neonates are infected with C difficile and most remain without symptoms. About 25 to 30 per cent of hospitalized adults are also C difficile carriers. These patients do not require any treatment.

Some patients have mild-to-moderate diarrhea, usually not bloody. At the other extreme, patients can be very seriously sick and have pseudomembranous colitis (see photograph). This is a serious condition and is a systemic illness. Patients have abdominal pain and tenderness, fever, and severe diarrhea that may be bloody. Marked elevations of the white blood count can be observed and may serve as a diagnostic clue. Bowel perforation is a very serious complication.

Oral metronidazole or oral vancomycin remains first-line therapy. Use of metronidazole in pregnancy remains controversial. Oral vancomycin is the only FDA-approved medication for the treatment of CDAD and can be used in pregnancy. Probiotics, to replace the good bugs in the gut, helps. Questran powder can be used to slow down the frequency of bowel movements. For intractable cases, stool transplant is an option.

Regardless, 12 to 24 per cent of patients develop a second episode of CDAD within two months of the initial diagnosis. If a patient has two or more episodes of CDAD, the risk for recurrences increases to 50 to 65 per cent.

Clearly, CDAD and C difficile infection pose a complex clinical challenge to the physician – whether the patient is pregnant or not.

Start reading the preview of my book A Doctor's Journey for free on Amazon. Available on Kindle for $2.99!