In my last article, I mentioned stool (fecal) transplant being an option in the management of intractable C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD). Your reaction must have been, “Yuck!”

“It’s a nasty topic to discuss but fecal transplants work – and I was not ready to wait any longer.” says a 66 year-old-man from Cape Breton (The Medical Post, April 24, 2012). The man gave himself a fecal infusion to try and rid himself of a C. difficile infection after being turned down for the procedure by Cape Breton Regional Hospital. His doctor’s reaction, “He did it himself? It’s not good to do by himself.”

Stool transplant (also called fecal bacteriotherapy), a procedure related to probiotic research, has preliminarily been shown to cure the disease. The procedure involves infusion of bacterial flora acquired from the feces of a healthy donor to reverse the bacterial imbalance responsible for the recurring nature of the infection in CDAD.

Bacteria make up most of the flora in the colon and up to 60 per cent of the dry mass of feces. Somewhere between 300 and 1000 different species live in the gut, with most estimates at about 500. According to Wikipedia, it is probable that 99 per cent of the bacteria come from about 30 or 40 species. Fungi and protozoa also make up a part of the gut flora, but little is known about their activities.

What is the function of these bacteria in our gut?

Humans and their bacterial flora have a non-harmful coexistence. The microorganisms perform a host of useful functions, such as fermenting unused energy substrates, training the immune system, preventing growth of harmful, pathogenic bacteria, regulating the development of the gut, producing vitamins for the host (such as biotin and vitamin K), and producing hormones to direct the host to store fats.

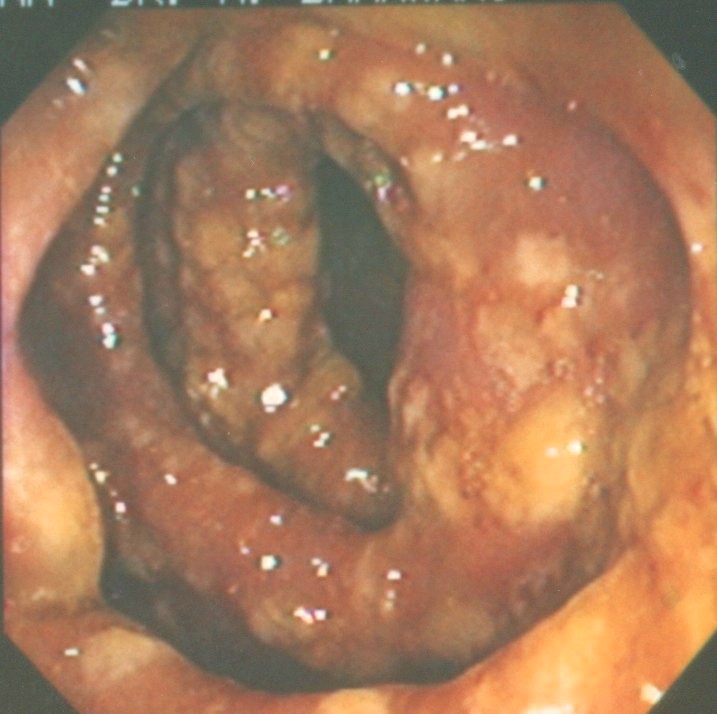

In fecal transplantation, donor stool is collected from a close relative who has been tested for a wide array of bacterial, viral, and parasitic pathogens. The stool is often mixed with saline or milk to achieve the desired consistency, then delivered through a colonoscope or retention enema, or through a nasogastric or nasoduodenal tube.

The idea is to replace normal, healthy colonic flora that had been wiped out by antibiotics, and reestablishes the patient’s resistance to colonization by Clostridium difficile.

Since 1958, more than 150 papers have been published on this subject. It has a success rate of about 90 per cent. A guide was released in 2010 for home fecal transplantation. Reports from many centres suggest that fecal transplants can be lifesaving for patients with recurrent CDAD.

In November, 2010, Alberta’s Institute of Health Economics released a report (Fecal Transplantation for the Treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated disease and/or ulcerative colitis) concluded that fecal transplant may restore normal bacterial flora, break the cycle of recurrent CDAD, usually after treatment failure with vancomycin therapy.

The report said, “The status of fecal transplantation as an experimental or accepted procedure for patients with recurrent CDAD remains to be determined.”

Currently, there are numerous studies going on to compare fecal transplant with other kinds of therapy in CDAD cases. The safety of the procedure needs to be clarified. Especially, now that the procedures are carried out in people’s homes rather than in the hospitals to avoid bureaucratic battles. Hopefully, we will have a definitive answer in the next few years.

Start reading the preview of my book A Doctor's Journey for free on Amazon. Available on Kindle for $2.99!