“Attacking people with disabilities is the lowest display of power I can think of.” -Morgan Freeman

Down syndrome is the most frequently occurring chromosomal congenital abnormality in Canada. It is a lifelong condition. It adversely affects infant’s life and mortality.

An English physician John Langdon Down first described Down syndrome in 1862, and helped to differentiate the condition from mental disability. Prior to that for centuries, people with Down syndrome have been alluded to in art, literature and science. Many individuals were killed, abandoned or ostracized from society. Many of these children died during infancy or early adulthood.

Humans usually have 46 chromosomes in every cell, with 23 inherited from each parent. Due to the extra copy of chromosome 21 (trisomy 21), people with Down’s syndrome have 47 chromosomes in their cells. This additional DNA causes the physical characteristics and developmental problems associated with the syndrome.

The cause of the extra full or partial chromosome is still unknown. Maternal age is the only factor that has been linked to an increased chance of having a child with Down syndrome. There is no definitive scientific research that indicates Down syndrome is caused by environmental factors or the parents’ activities before or during pregnancy.

The additional partial or full copy of the 21st chromosome that causes Down syndrome can originate from either the father or the mother. Approximately five per cent of the cases have been traced to the father.

Children with Down syndrome experience intellectual delays and are at an increased risk for several medical conditions.

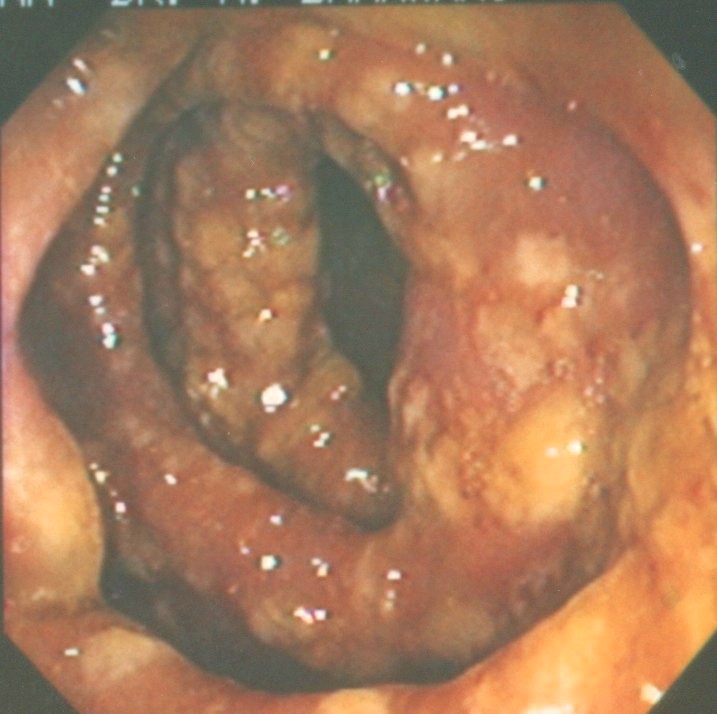

Congenital heart defects and respiratory infections are the most frequently reported causes of death in children and young adults with Down syndrome. Childhood leukemia is also associated with Down syndrome.

Due to higher birth rates in younger women, 80 per cent of children with Down syndrome are born to women under 35 years of age. Women aged 35-39 years have the highest percentage of babies born with Down syndrome (29 per cent).

According to a report on the Government of Canada website, the birth prevalence of Down syndrome in Canada from 2005 to 2013 has remained stable. Approximately one in 750 live born babies in Canada has Down syndrome. Advanced maternal age is the most significant risk factor, says the website.

Prenatal screening for Down syndrome has advanced in both accuracy and early detection. The number of children born with Down syndrome has remained stable due to increased use of prenatal diagnostic procedures followed by terminations of pregnancies.

The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada’s clinical care guidelines for prenatal testing advise against using maternal age as the only criterion for invasive prenatal diagnosis. They recommend prenatal screening for clinically significant fetal abnormalities be offered to all pregnant women, irrespective of age.

There are 45,000 Canadians with Down syndrome, with a very active organization, Canadian Down Syndrome Society (CDSS). The CDSS is a non-profit organization that provides Down syndrome advocacy in Canada, says their website.

The organization helps people with Down syndrome. People with Down syndrome can go to school, finish university, find careers, and get married. CDSS goal is to ensure all people with Down syndrome live fulfilled lives. It is Canada’s voice for Down syndrome.

Start reading the preview of my book A Doctor's Journey for free on Amazon. Available on Kindle for $2.99!