About 25 per cent of Canadian seniors suffer from three or more chronic illnesses and are on six or more medications per day.

One of the medications is Pantoloc. Pantoloc (pantoprazole) belongs to the family of medications called proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

First introduced in 1989, PPIs are among the most widely utilized medications worldwide, both in the ambulatory and inpatient clinical settings. These medications are central in the management of reflux disease and are unchallenged with regards to their efficacy.

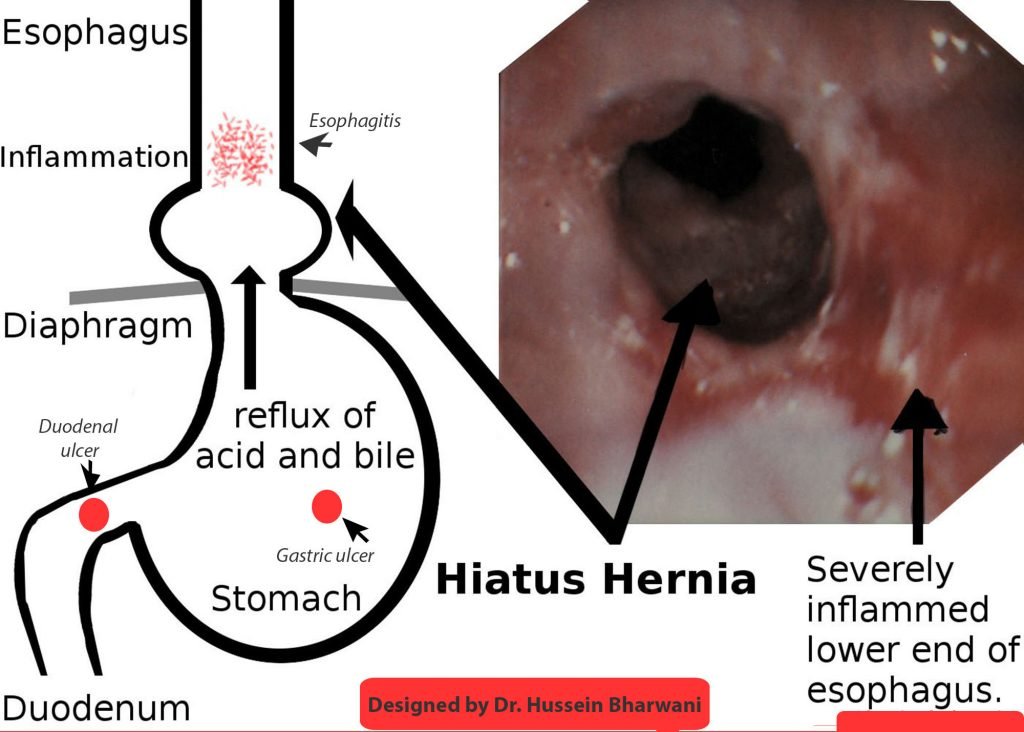

Pantoloc is the fifth most commonly prescribed drug. It is used for patients who have heartburn (GERD or gastro oesophageal reflux disease) or inflamed oesophagus (esophagitis). It is also used for peptic ulcer disease (duodenal or gastric ulcers).

The prevalence of heartburn and reflux disease increases with age and elderly are more likely to develop severe disease.

Treating inflamed oesophagus (esophagitis) due to reflux:

PPIs are indicated for short-term treatment of mild esophagitis. Treatment is usually for four to eight weeks duration. But if you have moderate esophagitis with endoscopic evidence of Barrett’s oesophagus (a premalignant inflammation of the oesophagus) and severe esophagitis grade C or D, then you need long-term to lifelong treatment with PPI.

Peptic ulcer disease

Peptic ulcer disease usually occurs in the stomach and proximal duodenum. It is caused by infection with Helicobacter pylori bacteria and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID).

Short-term PPI use for treatment of peptic ulcer disease is recommended for two to 12 weeks, unless maintenance therapy is clearly indicated, such as ongoing NSAID use.

If PPI is so effective then what is the problem. The problem is, and the studies have shown, once a patient is started on PPI, the symptoms are not reviewed and patients stay on them for years with no valid indication.

Long-term use of PPIs is not without risks, including vitamin B12 deficiency, osteoporosis, pneumonia and C. difficile associated diarrhea (colitis). A recent study suggests that the heartburn drugs may be associated with an increased risk of dementia and kidney disease.

What should patients and health care providers do?

There is an interesting website (deprescribing.org) that helps patients understand the rationale for deprescribing certain medications.

If the decision is made to deprescribe, the key to success is monitoring for rebound hyperacidity. Regular follow-up over the following four to 12 weeks is critical to assess for and manage adverse symptoms to deprescribing PPIs.

An article on the Mayo Clinic website by Avinash K. Nehra, MD et al titled “Proton Pump Inhibitors: Review of Emerging Concerns,” says that based on current recommendations, the American Gastroenterological Association does not recommend routine laboratory monitoring or use of supplemental calcium, vitamin B12, and magnesium in patients taking PPIs daily.

Nehra’s current practice is to check creatinine levels yearly, complete blood cell counts every other year, and vitamin B12 levels every five years in patients receiving long-term PPI therapy.

In summary, the best strategy is to prescribe PPIs at the lowest dose on a short-term basis when appropriately indicated so that the potential benefits outweigh any adverse effects associated with the use of PPIs, says Nehra.

Start reading the preview of my book A Doctor's Journey for free on Amazon. Available on Kindle for $2.99!