Dr. Noorali Bharwani comes to the awkward conclusion that as a surgeon he has certain skills but as for the general doctoring skills others seemed to have-uh, not so much.

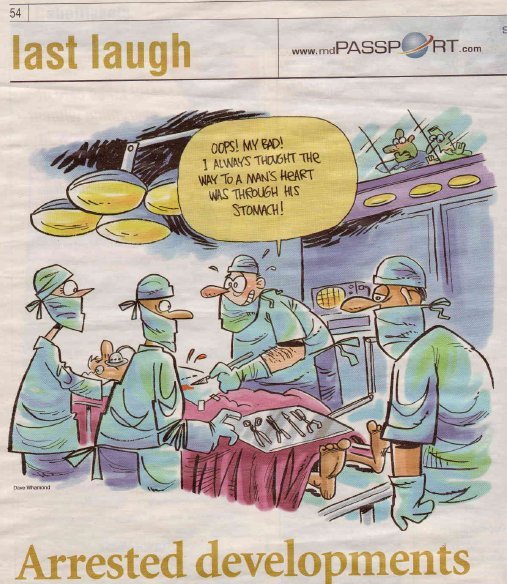

Cartoon from article in Medical Post.

When it comes to cardiac arrest, we, the surgeons, do not get any respect.

When it comes to severe trauma, a general surgeon is expected to be “captain of the ship” and take command of resuscitation and stabilization of the patient. This is because we know the first three letters of the alphabet: ABC (airway, breathing and circulation).

When I was a general surgical resident, I was not part of the cardiac arrest team. I confess, beyond ABC, I have difficulty remembering what to inject and where to inject drugs during cardiac arrest. Should they be given subcutaneously, intravenously or intra-cardiac? What does the ECG say? I can read a flat line (by that time it is too late anyway) but I would have trouble interpreting anything else.

I am not totally useless. I can intubate a patient, perform a tracheotomy, do a cut down on a vein and place an arterial line. Beyond that my medical knowledge is not that strong.

I was beginning to develop a complex. I was jealous of the internal medicine residents who acted so smart. Their white coat pockets bulged with concise pocket guidebooks, hammer, tuning fork, flashlight, different coloured pens and a stethoscope hanging down their necks. They would know the precise dosage of medications and would know exactly what to give at what stage of the cardiac arrest.

In order to regain my confidence and self-esteem, I decided to do three months’ elective in ICU as part of my surgical residency program.

Word of my limited knowledge of cardio-respiratory medicine must have reached the medical staff of ICU because the only procedures I was assigned to do were tracheotomies, intubations, cut-downs for venous excess and insertion of an arterial line.

This further exasperated my frustration and low personal esteem. It did not get any better when I went into practice. One day, I had done a right hemicolectomy on an elderly patient. Within the first couple of days after surgery, he developed severe chest pain and went into cardiac arrest. This was about two in the morning. The nurse phoned me to say the cardiac arrest team was there to resuscitate the patient and she was letting me know what was going on. She said the ER physician was dealing with the cardiac arrest.

I felt guilty that I wasn’t there to be “captain of the ship” and save my patient’s life. By the time I dressed and rushed to the hospital the patient had died. I could see the straight line on the ECG, the pupils were fixed and dilated, he was not responding to painful stimuli, he had no heart or breath sounds. Like a true captain I called off the resuscitation process.

Last summer, I was on a transatlantic flight with my family. I was trying to relax with soft jazz music beaming through my earphones. Suddenly the music stopped and I heard the captain say: “This is the captain speaking. Is there is a doctor or a nurse on board? Please identify yourself.”

I was reluctant to identify myself knowing my limited capacity when dealing with medical problems. At the request of my family, and not wanting my children to see me being a wuss, I pressed the overhead button. The air hostess came.

“I am a surgeon. Is there anything I can do to help?” I asked.

“Oh, don’t worry,” she said. “We don’t think the lady needs any surgery. She is having chest pain and is short of breath. We found a nurse. She is managing the case quite well.”

Although I was relieved to hear everything was going well without my services, I wondered what would have happened if my services were needed. Would I have failed to save somebody’s life?

That question weighed heavily on my chest (no pun intended). I started to get nightmares. In my sleep, I would recite the protocol of managing cardiac arrest. One night, my wife shook me and woke me up. Apparently, I was trying to give her mouth-to-mouth resuscitation while massaging her chest. She said I had been doing that every night since we got back from our holidays. Except, this time I was getting a little too excited!

“Honey, you don’t have to be that rough. If you want something then just ask nicely,” she said.

Why didn’t she say that before?

Start reading the preview of my book A Doctor's Journey for free on Amazon. Available on Kindle for $2.99!